09.03.2009 13:06

Twenty-five years ago, the Tory government led by Margaret Thatcher declared war on the National Union of Mineworkers. The Tories had been preparing for a showdown with the NUM since before the 1979 general election. They could not forget the victorious miners' strikes of 1972 and 1974, the second of which had brought down the Tory government in a general election.

But the NUM's historic battle did not begin in March 1984, as so many pundits claim. The seeds of the dispute had been sown long before. A pit closure plan in 1981 resulted in miners, including miners in Nottinghamshire, taking unofficial strike action (without a ballot) and forcing Thatcher into a U-turn, or in reality a body swerve.

At that time, Britain's coal industry was the most efficient and technologically advanced in the world, a result of a tripartite agreement, the Plan For Coal, signed by a Labour government, the National Coal Board (NCB) and the mining trade unions in 1974, and endorsed by Thatcher in 1981. And yet, shortly after I became national president of the NUM in 1982 I was sent anonymously a copy of a secret plan prepared by NCB chiefs earmarking 95 pits for closure, with the loss of 100,000 miners' jobs. This plan had been prepared on government instructions following the miners' successful unofficial strike in 1981.

I took this document to the union's National Executive Committee (NEC) - its contents were not only denied by government and NCB chiefs, but were disbelieved by militant NUM leaders who had been assured that their pits had long-term futures. However, the exposed revelations struck a chord among our members throughout Britain's coalfields where colliery managers - clearly acting on instructions from above - had already begun unilaterally changing agreed working practices, affecting shift patterns and supplementary payments.

It became clear that the union would have to take action, but of a type that would win maximum support and have a unifying effect. The NEC accepted a report from me recommending that we call a special national delegate conference, and link our opposition to the pit closure plan with a demand that the coal board negotiate the union's wage claim. The NEC agreed, and the special conference was held on 21 October 1983. Delegates from all NUM areas were given a detailed report so that they could vote on what action - if any - should be taken. Following a full debate, they agreed to call a national overtime ban from 1 November - until such time as the NCB withdrew its closure plan and agreed to negotiate an increase in miners' wages with the NUM.

Over the next four months, the overtime ban had an extraordinary impact. It succeeded in reducing coal output by 30%, or 12m tonnes, thus cutting national coal stocks to about the same level as they had been during the miners' unofficial strike in 1981.

Then, on 1 March 1984, acting I believe on national instruction, NCB directors in four areas announced the immediate closure of five pits: Cortonwood and Bullcliffe Wood in Yorkshire, Herrington in Durham, Snowdown in Kent and Polmaise in Scotland.

Coalfield reaction was electrifying. On Saturday 3 March, accompanied by the NUM Yorkshire president, Jack Taylor, I spoke at a packed meeting in South Yorkshire initially organised to discuss various issues that had already brought seven Yorkshire pits out on strike. I knew we had to do everything possible to persuade our members to direct their rage in a united way at the pit closure plan and its threat to butcher our industry.

On Sunday evening Taylor and I attended a Yorkshire Brass Band Festival in Sheffield city hall. By then I had consulted my fellow national officials, the vice-president, Michael McGahey, and the national secretary, Peter Heathfield.

It was essential to present a united response to the NCB and we agreed that, if the coal board planned to force pit closures on an area by area basis, then we must respond at least initially on that same basis. The NUM's rules permitted areas to take official strike action if authorised by our national executive committee in accordance with Rule 41. If the NEC gave Scotland and Yorkshire authorisation under this rule, it could galvanise other areas to seek similar support for action against closures.

During an interval in the concert, I used the back of a programme to draft a strike resolution which I asked Taylor to present the following morning to the Yorkshire area council meeting. I told him that McGahey would be doing the same thing at the same time in Scotland.

On 6 March, at a consultative meeting at NCB London headquarters, the coal board chairman, Ian MacGregor, not only confirmed what we had been expecting, but announced that in addition to the five pits already earmarked for immediate closure, a further 20 would be closed during the coming year, with the loss of more than 20,000 jobs. This, he said, was being done to take four million tonnes of "unwanted" capacity out of the industry, and bring supply into line with demand.

The Scotland and Yorkshire NUM areas did vote to seek endorsement from the NEC for strike action, and at the NEC meeting on 8 March were given authorisation under Rule 41. South Wales and Kent then also asked for authorisation. The NEC agreed, and confirmed that other areas could, if they wished, do the same. We realised that the NCB announcement on 6 March had amounted to a declaration of war. We could either surrender right now, or stand and fight.

A question that has been raised time and time again over the past 25 years is: why did the union not hold a national strike ballot? Those who attack our struggle by vilifying me usually say: "Scargill rejected calls for a ballot."

The real reason that NUM areas such as Nottinghamshire, South Derbyshire and Leicestershire wanted a national strike ballot was that they wanted the strike called off, believing naively that their pits were safe.

Three years earlier, in 1981, there had been no ballot when miners' unofficial strike action - involving Notts miners - had caused Thatcher to retreat from mass closures (nor in 1972 when more than a million workers went on strike in support of the Pentonville Five dockers who had been jailed for defying government anti-union legislation).

McGahey argued that the union should not be "constitutionalised" out of taking action, while the South Wales area president, Emlyn Williams, told the NEC on 12 April 1984: "To hide behind a ballot is an act of cowardice. I tell you this now ... decide what you like about a ballot but our coalfield will be on strike and stay on strike."

However, NUM areas had a right to ask the NEC to convene a special national delegate conference (as we had when calling the overtime ban) to determine whether delegates mandated by their areas should vote for a national individual ballot or reaffirm the decision of the NEC to permit areas such as Scotland, Yorkshire, South Wales and Kent to take strike action in accordance with Rule 41.

Our special conference was held on 19 April. McGahey, Heathfield and I were aware from feedback that a slight majority of areas favoured the demand for a national strike ballot; therefore, we were expecting and had prepared for that course of action with posters, ballot papers and leaflets. A major campaign was ready to go for a "Yes" vote in a national strike ballot.

At the conference, Heathfield told delegates in his opening address: "I hope that we are sincere and honest enough to recognise that a ballot should not be used and exercised as a veto to prevent people in other areas defending their jobs." His succinct reminder of the situation we were in opened up an emotional debate to which speaker after speaker made passionate and fiercely argued contributions.

Replying to that debate, I said: "This battle is certainly about more than the miners' union. It is for the right to work. It is for the right to preserve our pits. It is for the right to preserve this industry ... We can all make speeches, but at the end of the day we have got to stand up and be counted ... We have got to come out and say not only what we feel should be done, but do it because if we don't do that, then we fail."

McGahey, Heathfield and I had done the arithmetic beforehand, and were truly surprised that when the vote was taken, delegates rejected calls for a national strike ballot and decided instead to call on all miners to refuse to cross picket lines - and join the 140,000 already on strike. We later learned that members of one area delegation had been so moved by the arguments put forward in the debate that they'd held an impromptu meeting and switched their vote in support of the area strikes in accordance with Rule 41.

During the strike I was also criticised, indeed attacked - by my own colleagues - for arguing that the NUM's prime picketing targets should be power stations, ports, cement works, steelworks and coking plants. But evidence now available shows my argument was correct.

My passionate conviction that the Orgreave coking plant in South Yorkshire should be selected as a main target was rubbished at the time. Yet, it has now been revealed from official sources that show coal stocks at steel plants - particularly Scunthorpe in Yorkshire, Ravenscraig in Scotland and Llanwern in Wales - were so low that these works could only continue in production for a matter of weeks, with Scunthorpe - where British Steel had already laid off 160 workers due to coal shortages - actually earmarked for closure by 18 June 1984.

The issue of dispensations that would allow provision of coal supplies created divisions among the most militant sections of the NUM. I had argued passionately that there should be no dispensations for power stations, cement works, steelworks or coking plants, whose coal stocks were extremely low.

Many on the union's left - particularly those in the Communist party - argued that the union had a responsibility to ensure that a minimal amount of coal could be delivered in order to keep the giant furnaces and ovens "ticking over". Heathfield and a number of others on the NUM left agreed with me that there should be no dispensations and that if steelworks had to close down, as British Steel's chairman, Bob Haslam, warned was inevitable, then the responsibility lay firmly at the door of the government, not the NUM.

Despite the passionate arguments made by Heathfield and myself, areas did give dispensations. Two months went by before it dawned on Yorkshire, South Wales and Scotland that they had been outmanoeuvred by British Steel, and the leadership of the steelworkers' union, and that British Steel was moving far more coal than the dispensations agreed with NUM areas. Yet there was still time to stop all those giant steelworks, and if the steelworkers' union would not cooperate with the NUM to stop all deliveries of coal to the steelworks then the National Union of Seamen and rail unions Aslef and NUR had already demonstrated that they would stop all deliveries.

The scene was set for the battle of Orgreave.

Orgreave coking plant was a crucial target for mass picketing. I knew that its coal supplies could be cut off as had been the case at the Saltley coke depot in Birmingham in 1972 - a turning point after which that strike was soon settled.

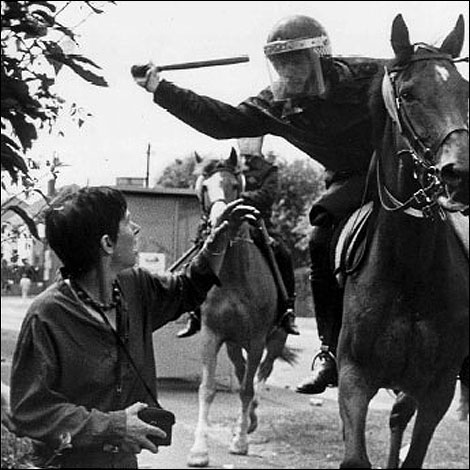

Contrary to popular mythology, Orgreave was closed twice: first on 27 May 1984, when together with dozens of others I was injured on the picket line. Second, on 18 June, when 10,000 pickets faced 8,500 riot police in a scene reminiscent of a battle in England's 17th-century civil war.

So fierce was the conflict on 18 June that dozens of pickets were hospitalised (including me), but the picketing resulted in British Steel's chairman sending a telex closing down Orgreave on a temporary basis - exactly as had been the case at Saltley coke depot in Birmingham 12 years before.

The fundamental difference between Saltley in 1972 and Orgreave in 1984 was that in 1972 following the first closure at Saltley, picketing on my demand was increased the following day - while at Orgreave, on 19 June 1984, the pickets were completely withdrawn by the NUM Yorkshire and Derbyshire areas and other coalfield leaders, despite my desperate urging that picketing be stepped up.

Had picketing at Orgreave been increased the day after 18 June, I have no doubt that Orgreave - and Scunthorpe - would have faced immediate closure, forcing the government to settle the strike.

For 25 years, I have been accused of refusing to negotiate a settlement with the NCB, and of "snatching defeat from the jaws of victory" - a blatant lie. The NUM settled the strike on five separate occasions in 1984: on 8 June, 8 July, 18 July, 10 September, and 12 October. The first four settlements were sabotaged or withdrawn following the intervention of Thatcher.

The most important settlement terms were agreed between leaders of the pit deputies' union Nacods and the NUM at the offices of the conciliation service Acas on 12 October 1984 and included a demand that the NCB withdraw its pit closure plan, give an undertaking that the five collieries earmarked for immediate closure would be kept open, and guarantee that no pit would be closed unless by joint agreement it was deemed to be exhausted or unsafe.

Nacods members had recorded an 82% ballot vote for strike action, and their leaders made clear to the NCB that unless the Nacods-NUM terms were accepted, the Nacods strike would go ahead.

I was later told by a Tory who had been a minister at the time that when Thatcher was informed of the Nacods-NUM agreement she announced to the cabinet "special committee" that the government had no choice but to settle the strike on the unions' terms.

However, when she learned that Nacods - despite pleas from the TUC and the NUM - had called off their strike and accepted a "modified" colliery review procedure, she immediately withdrew the government's decision to settle. Nacods' inexplicable decision led to the closure of 164 pits and the loss of 160,000 jobs.

The monumental betrayal by Nacods has never been explained in a way that makes sense. Even the TUC recognised that the Nacods settlement was a disaster.

The fact that Nacods leaders ignored pleas from the NUM and TUC not to call off their strike or resile from their agreement with the NUM not only adds mystery but poses the question - whose hand did the moving, and why?

Over the years, I have repeatedly said that we didn't "come close" to total victory in October 1984 - we had it, and at the very point of victory we were betrayed. Only the Nacods leaders know why.

A full account of the strike of 1984/85 is still to be written. However, we have learned more and more about the then Labour party leader, Neil Kinnock's treachery, the betrayals by the TUC and the class collaboration of union leaders such as Eric Hammond (the electricians' EETPU) and John Lyons (Engineers and Managers Association), who instructed their members to cross picket lines and did all they could to defeat the miners.

We have also seen how many who, like Kinnock, bleated constantly about the need for a ballot during the miners' strike didn't call for the British people to have a ballot in 2003 when Tony Blair took the nation into an unlawful war and the occupation of Iraq.

During the past 25 years, many who have attacked the NUM, and me, about the need for a ballot, or argued that we selected the wrong targets have done so to cover their own guilt at failing to give the miners a level of support that would have stopped the Tories' pit closure programme and thus changed the political direction of the nation. Britain in 1984 was already a divided and degraded society - it has become much more so in the 25 years since.

The NUM's struggle remains not only an inspiration for workers but a warning to today's union leaders of their responsibility to their members, and the need to challenge both government and employers over all forms of injustice, inequality and exploitation.

That is the legacy of the NUM's strike of 1984/85, a truly historic fight that gave birth to the magnificent Women Against Pit Closures and the miners' support groups. I have always said that the greatest victory in the strike was the struggle itself, a struggle that inspired millions of people around the world.

• On 12 March, at 7.30pm, Arthur Scargill will be speaking on the lessons of the 1984/85 miners' strike at the Conway Hall, Red Lion Square, London, WC1

Arthur Scargill

Homepage:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/2009/mar/07/arthur-scargill-miners-strike

Homepage:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/2009/mar/07/arthur-scargill-miners-strike

http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2009/mar/06/miners-strike-1984-85-margaretthatcher , has joined a long line of media commentators who have used the 25th anniversary of the start of the 1984 miners strike to pour excreta over Arthur Scargill. With their demonization of Scargill it is difficult not to conclude the media’s main aim is to re-write the history of the strike. Reading these articles you will need to look hard to find a condemnation of Thatcher, or the then LP leader Neil Kinnock's disgraceful betrayal of trade unionists in struggle.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2009/mar/06/miners-strike-1984-85-margaretthatcher , has joined a long line of media commentators who have used the 25th anniversary of the start of the 1984 miners strike to pour excreta over Arthur Scargill. With their demonization of Scargill it is difficult not to conclude the media’s main aim is to re-write the history of the strike. Reading these articles you will need to look hard to find a condemnation of Thatcher, or the then LP leader Neil Kinnock's disgraceful betrayal of trade unionists in struggle.

Homepage:

Homepage:

Comments

Display the following 5 comments